“Aligning with the concept of ikigai: what we love, what we are good at, and what the world needs…”

Human of Medicine #48

This publication is in conjunction with the public health initiative by MMI aimed at fostering digitalisation and entrepreneurship among healthcare leaders, particularly in the aspect of telemedicine. Further information can be found at @mmi_social on Instagram.

Dr. Ginsky Chan is the Access Director at Angsana Health, a Malaysian company that delivers digital health services and systems in Southeast Asia. He earned his Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) from the Sri Devaraj Urs Medical College and a Master of Public Health (MPH) with a specialized stream in Health Economics from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, University of London. Before his current role, Dr. Ginsky Chan gained valuable experience working as a house officer and medical officer with the Malaysian Ministry of Health (KKM).

Most of us have the same inspiration for why we want to become doctors, and it is rarely for financial gain. My inspiration to become a doctor was fueled by a strong desire to make a difference. Growing up, my volunteer work at my church exposed me to the fulfillment of helping others. At that time, given my limited knowledge, a career in medicine was the most impactful way to answer my calling. With all that I am blessed with, I feel a strong duty to help others.

The Shift from “Traditional” Healthcare to Digital Health

In “traditional” healthcare settings, physical constraints and one-on-one patient interactions often restricted my impact. To create a greater impact, I pursued a Master’s in Public Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. However, I soon realized that public health still faced similar limitations. The breakthrough came with digital health. Digital health offers the potential to scale and benefit thousands or even millions of patients, which became my main motivation for transitioning from “traditional” healthcare.

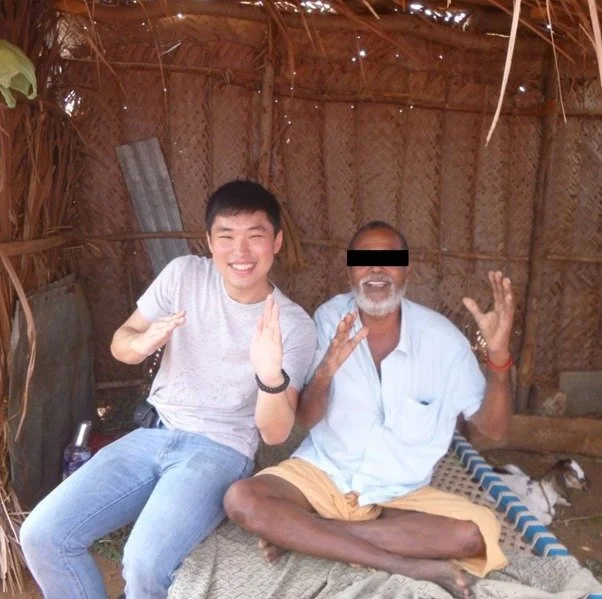

Serving rural Oddanchatram, Tamil Nadu. Notice how this person's bedroom is also the barn

The COVID-19 pandemic was a pivotal moment in my career. My experiences in both India and Malaysia exposed me to healthcare gaps and inequities across various settings—urban and rural, private and public. I witnessed the power of telehealth services during lockdowns, which kept patients connected to their healthcare providers. This realization drove me to join a talented team to establish Angsana Health. Our goal was to provide continuous quality care, regardless of circumstances like COVID-19.

Securing funding is challenging, but finding the right product-market fit is even more crucial. In healthcare, the decision-maker, payer, and user of the services are often different entities. For instance, a cancer patient receives treatment based on a doctor’s recommendation, paid for by an insurance company or government subsidy. This complexity contrasts with consumer products like iPhones, where the decision-maker, payer, and user are typically the same person. My training in health economics, gained during my Master’s in Public Health, has been invaluable in addressing these multi-stakeholder challenges and ensuring that our solutions meet the needs of all parties involved.

Smiling for the photograph despite the exhaustion of being a frontliner during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our services at Angsana Health are driven by three key factors: passion, expertise, and need. Our team includes members with personal experiences related to the conditions we address, such as dementia, autism, tuberculosis, and non-communicable diseases. We have a highly qualified team, including 21 medical doctors and six specialists out of 38 colleagues, with an average of 10 years of work experience. We focus on addressing significant health needs in Malaysia and Southeast Asia, aligning with the concept of ikigai: what we love, what we are good at, and what the world needs.

Building a Team and Approach to Entrepreneurship

Building a team for digital health was challenging because the field was—and still is—relatively new, making it difficult to find experts who excel in healthcare and technology. One key insight was recognizing that individuals with expertise in both fields are rare. At Angsana Health, our team comprises doctors, speech therapists, dieticians, and other healthcare professionals, as well as experts in law, marketing, finance, technology, and business. Given the polar difference in backgrounds, speaking the same language is crucial. Translating medical jargon into layperson terms is important to facilitate better communication and collaboration. Internally, we refer to those unfamiliar with medical jargon as the “Non-Doctors Coalition” (NDC) to consciously remind ourselves to speak the same language.

My background in medicine and public health shapes my entrepreneurial approach in three key areas: effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and humanity.

Effectiveness: Every service we develop must deliver positive outcomes for patients. For instance, our solutions may directly reduce risks, such as falls among the elderly, or indirectly shorten waiting times for interventions, like reducing delays for children with an autism spectrum disorder to begin intervention.

Cost-Effectiveness: Our services are designed to reduce costs beyond improving health outcomes. A prime example is our digital health service for tuberculosis patients, which allows them to be monitored at home rather than having to travel daily to a clinic. This virtual observation cuts patient travel expenses and frees up healthcare providers' time, allowing them to attend to other pressing needs. Thus, our service offers both patient and provider cost savings.

Humanity: We prioritize patient experience by balancing public health protection with respect for individual dignity. For example, while traditional methods require tuberculosis patients to visit a clinic for medication monitoring—a practice that can be stigmatizing—we offer a home-based, virtual solution. This approach safeguards public health while respecting patient autonomy and reducing the stigma associated with in-person visits.

The team behind Angsana Health

Navigating Regulations and Infrastructure in Southeast Asia

Regulations and standards for digital health solutions in Southeast Asia, including Malaysia, are still developing. Although regulatory frameworks exist, they are nascent. Knowledge alone is not enough; it must be effectively implemented. To address this, my team and I prioritize understanding regional regulations and standards and are committed to continuous education. We have established an infrastructure that includes a legal and ethics officer and codes of business and AI conduct. These measures ensure that our knowledge is applied in practice. Additionally, we have set up a monitoring and feedback mechanism to proactively identify and address regulatory issues, ensuring compliance with all relevant standards.

Regulations for digital health services vary significantly across Southeast Asian countries. For example, in Singapore, telemedicine consultations can result in the issuance of medical certificates, whereas in Malaysia, medical certificates can only be issued following a physical consultation. This highlights a major regulatory difference. Another example is the restriction on cross-border telemedicine; a doctor in Brunei cannot legally treat a patient in the Philippines via telemedicine due to differing national regulations and recognition of medical training.

Cost-effectiveness thresholds for healthcare services differ from country to country. This threshold represents the maximum amount a country is willing to pay for a unit of health outcome improvement. For instance, Malaysia has about 10-11% of its population aged 60 and above, while Singapore has approximately 24%. This disparity means Singapore may be more willing to invest in services for senior citizens due to a larger population benefiting from the service, illustrating how economic factors impact healthcare service adoption across the region.

Infrastructure, particularly internet connectivity, is crucial in implementing digital health services. For example, while Malaysia has about 25,000-26,000 tuberculosis cases annually, Indonesia, with a much larger population, has around 1 million cases. Despite the large health burden, the rollout of digital health services in Indonesia can be limited by its vast geography and uneven internet access, with many areas lacking reliable connectivity. Therefore, all things being equal, countries with better internet infrastructure are better positioned to implement digital health solutions effectively.

Arulselvi Manoharan is a medical graduate from Management & Science University.

Medicine is the fusion of science, technology, and art towards hope of life. Through writing, we empower it further.

Goh Li Lian is an aspiring medical student at IMU University.

In healthcare, we are united not only by action, but also words of intellect and altruism.

Consent has been obtained from the interviewee for the purpose of this publication. The author has rewritten the article with permission from the interviewee.

Humans of Medicine is a new initiative under MMI. We tell inspiring stories behind portrait shots of our everyday unsung heroes. Curated by Malaysian medical students from home and abroad.

If you have a story you would like to share, please reach out to us at admin@malaysianmedics.org.